Top 3 Accessibility Barriers to Civic Participation

Source: “WTC Member and Partner Organizations Accessibility Survey” conducted in June 2025.

Over a quarter of BC’s population lives with at least one disability; many of which experience poverty at twice the rate of those without disabilities. A majority of people with disabilities (PWD) often encounter barriers to accessibility that limit their ability to participate fully in civic life.

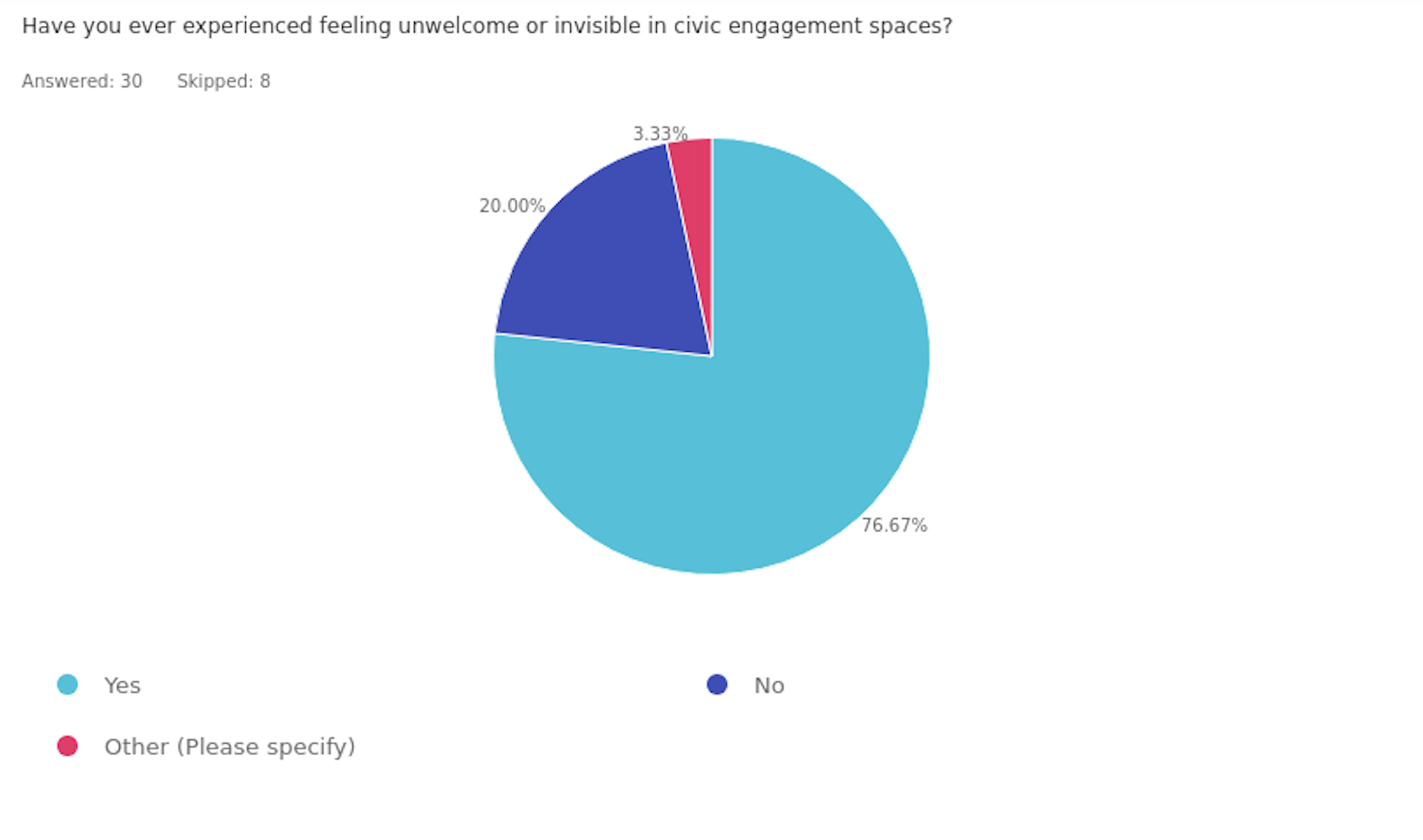

In June, WTC conducted a local survey where we heard from 30 WTC members and community partners with disabilities about the challenges and barriers they face in civic spaces.

The results were clear and consistent with what we know from disability justice advocates: 75% of participants said they have felt unwelcome or invisible in civic spaces.

Here are some of the common themes from our survey to help us understand why civic spaces do not feel welcoming for PWD:

Communication is unclear and at times confusing

More than half of survey participants expressed that communication about civic processes and what is happening at council is often unclear and confusing. Information about accessibility is not always kept up to date, nor is it easy to find online. People also mentioned that jargon—terms like by-law, resolution, ordinances - and the heavy use of acronyms can feel exclusionary and hard to understand when navigating civic spaces.

A need for more accommodation

Participants cited many ways that civic spaces fail to meet their needs. This included expecting people to walk long distances to access spaces and not accommodating fat bodies. Places like city hall were also described as high sensory (loud and busy) which can be overwhelming and discouraging, especially for those who are neurodivergent.

Living with disability and mental health flare-ups

Living with disabilities also means fluctuations in energy and mental health. This makes civic participation such as attending all candidates' meetings, community consultations or voting, when flare-ups occur much harder. These challenges highlight the need for flexible accessible options to participate that account for the lived experience of PWD.

Ableism is a major barrier to civic participation in municipal government for PWD, and disability justice is a useful framework to overcome that by placing the lived experiences of disabled, Black, Indigenous, racialized, queer, unhoused, and incarcerated people at the centre.

This framework was coined by Sins Invalid, a performance project and Disability Justice-based movement of disabled queer women of colour including Patty Berne, Mia Mingus, and the late Stacy Milbern. Disability justice builds on the disability rights movement, but recognizes the intersections of ableism with other issues such as race, colonialism, gender, sex, and capitalism.

At our “Disability Justice and Local Government: Tools for Change” workshop in July, we discussed barriers to participation with attendees and collaborated on potential solutions such as:

More flexibility in scheduling and forms of participation in council meetings

While each city council sets its own schedule, public meetings can be scheduled during work hours or in the evening when childcare is not available. Speakers or delegations can phone in, but it can be difficult to predict when speaking time will begin. Having a set speaking time and being able to comment virtually could potentially improve access and attendance.

Hiring more PWDs as city staff

“Leadership of the most impacted” is one of the ten principles of Disability Justice. It emphasizes that decision-making power should be held by those most affected by oppression or injustice. Hiring more PWDs with intersecting identities not only enriches the diversity of perspectives in the workplace, but also recognizes them as the experts of their own lives, transforming the status quo by placing their experiences at the centre.

Providing low sensory options at civic events

Civic spaces can often be loud and overwhelming. Providing low sensory options like ‘quiet’ voting areas or a low-sensory tent at events are some ways of accounting for neurodiversity. Quiet areas benefit most, not only those who are neurodivergent. When we are able to retreat for a short time, we can re-engage in a positive way.

These suggestions came out of participant discussions and provide insight into what accommodations are lacking in civic spaces but also highlight what changes that PWDs would like to see in order to show up more fully in local government.

WTC will continue to advocate for changes to civic processes and spaces so that everyone can participate in creating a city where they belong.

When a quarter of the population of the province lives with a disability—think about how many people we aren’t hearing from, and aren’t involved in shaping their communities and cities to be places where they can belong, participate and thrive.

To book our workshop on disability justice and local government, contact Florence at florence@womentransformingcities.org.